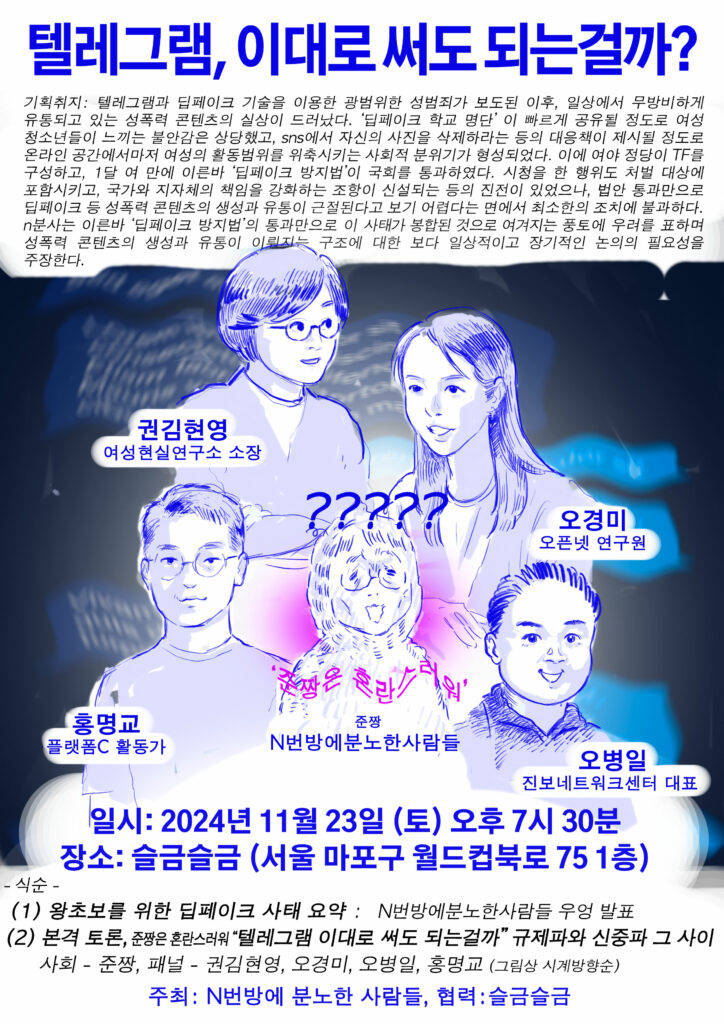

On November 23rd, Open Net Researcher Kyoungmi (Kimmy) Oh participated as a panelist in a discussion titled “Is it okay to use Telegram as it is?” hosted by “People Outraged by Nth Room Incident.”

- Moderator: Jun-jjang

- Panelist: Kwon Kim Hyun-young (Women’s Reality Research Institute), Hong Myeong-gyo (Platform C), Oh Byeong-il (Korean Progressive Network Jinbonet), Oh Kyoungmi (Open Net Korea)

Here are Kimmy’s answers to the main questions discussed during the debate:

1. Is there a need for an international consensus to address the cross-border issue of deepfake sexual exploitation?

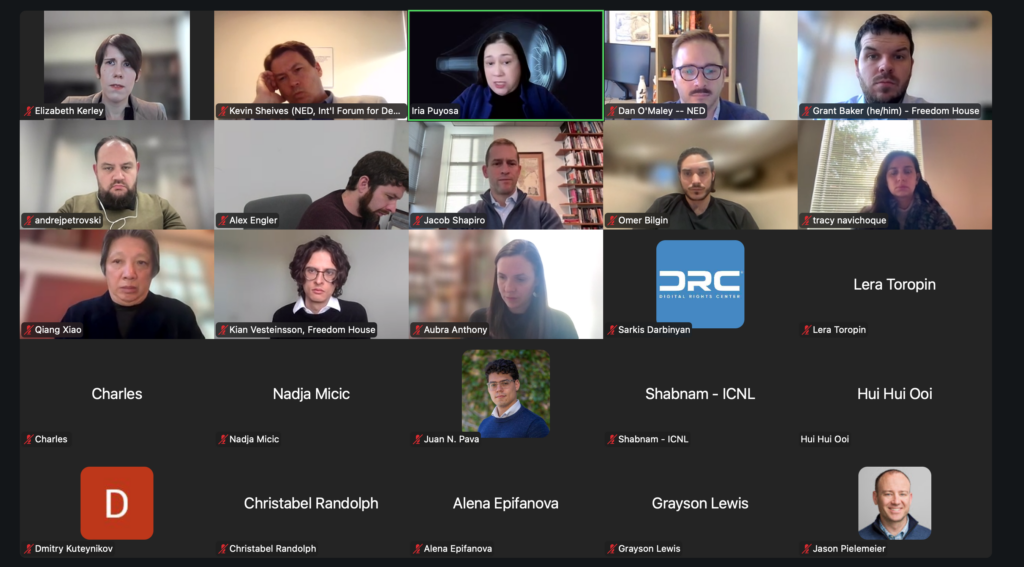

Overseas civil society organizations, particularly those advocating for women’s rights, are actively working together to raise awareness of gendered disinformation targeting women activists and journalists. They participate in international events, highlight the seriousness of the issue, carefully address differing social contexts in each country, plan sessions, and co-author related reports.

These international collaborations among women’s organizations have influenced the UN and major nations to consider these issues at the policy-making stage. They have also prompted media outlets to reflect on their reporting practices, leading journalists to acknowledge their unintended role in spreading gendered disinformation and reevaluate their approaches.

South Korea is presumed to lead in the frequency and scale of deepfake sexual crimes. According to a report by the cybersecurity firm Security Hero, 53% of women depicted in deepfake crimes last year were predominantly Korean singers and actors. However, activists from international digital rights organizations also express concern about the growing prevalence of deepfake sexual crimes in Southeast Asia.

It is essential to create forums for discussion to build solidarity, identify short- and long-term solutions, and determine the key stakeholders who must be involved in addressing the problem.

2. Is it essential for the introduction and expansion of comprehensive sex education to prevent deepfake sexual exploitation?

This solution is critically needed. In addition to comprehensive sex education, media literacy education should also be implemented. There is a proposal to integrate comprehensive sex education into media literacy education.

3. Do we need to regulate AI technologies that could potentially be used to create deepfake sexual exploitation materials?

The current state of AI technology has many issues, and efforts should focus on addressing its blind spots to ensure it benefits vulnerable populations. Mechanisms such as impact assessments before and after commercialization should be enforced to compel developers to improve their technologies.

However, the question of how to regulate AI to prevent it from directly generating sexual exploitation content requires careful consideration. AI technology simulates human intelligence and problem-solving, allowing machines to process massive amounts of data and generate outputs tailored to user requests. Consequently, AI systems capable of generating images, videos, or language-based content inherently possess the potential to create deepfake materials. Like a knife, which can be a useful tool or a weapon depending on its use, AI must be understood in this dual context.

If regulation alone is seen as the solution due to concerns about misuse, one extreme approach would involve eradicating all potentially exploitable data, such as nude images or explicit descriptions, from the internet. However, this method is practically unfeasible. Moreover, the harm caused by deepfake sexual crimes stems from the societal vulnerability of women’s sexuality compared to men’s. Removing all expressions related to women’s sexuality may not effectively address the underlying issue of their vulnerability.

4. Do you think there is a need for national regulation of platforms to prevent deepfake sexual exploitation?

Deepfake materials created using the likeness of real individuals are clearly illegal content and must be regulated. South Korea already enforces regulations on illegal content through laws such as the Information and Communications Network Act, the Juvenile Protection Act, the Special Act on Sexual Violence, and the Criminal Code. Recent cases have led to the addition of deepfake-specific provisions to the Special Act on Sexual Violence, and technologies like illegal content filtering on platforms like KakaoTalk have been implemented. Platforms are required by law to immediately remove illegal content upon recognition.

However, there is concern that regulation is being overly emphasized as the only solution. Discussions often center on platform regulation whenever a crime involving platforms occurs, but platform regulation alone cannot address the issue comprehensively. A multi-faceted analysis is necessary. For instance, what societal factors enable deepfake sexual crimes? What structural issues hinder or complicate victims’ recovery?

While strengthening platform accountability is crucial, excessive regulation can have unintended consequences. For instance, stricter regulations often require platforms to preemptively and retrospectively censor all content, increasing operational costs and potentially barring new market entrants. This could lead to monopolization by a few established platforms.

Digital rights activists also worry that platform regulation may lead to increased personal data collection. For example, South Korea’s 2021 proposal to revise the Electronic Commerce Act would have required platforms to verify and store the identity information of individual sellers to ensure consumer protection. Critics argued this could function as a de facto internet real-name system, undermining privacy and raising constitutional concerns.

If platforms collect users’ data, there are additional risks. For instance, governments could misuse such data for unethical purposes. While protecting vulnerable groups is a valid justification for regulation, dismissing these concerns as merely ethical dilemmas overlooks the potential dangers. Countries like Vietnam have pressured platforms through covert means, such as throttling traffic, to extract desired information or enforce compliance. Such scenarios highlight the risks of excessive platform control and underline the need for balanced, thoughtful regulation.

5. Should the police be able to request platforms to remove digital sexual violence content without going through the Korea Communications Standards Commission?

Allowing the police to request the removal of digital sexual violence content directly from platforms without going through regulatory bodies like the Korea Communications Standard Commission (KCSC) could have significant implications. While it is not inherently problematic for the police to notify platforms about the presence of illegal content, concerns arise when platforms are held civilly or criminally liable for not immediately complying with such requests, especially if they are assessing the legality of the content. Determining whether content is illegal should not fall solely under the jurisdiction of administrative agencies. There is a risk that the police, acting as a secondary censorship authority, could inadvertently strengthen state censorship. Therefore, the police’s role should be limited to providing information to platforms rather than enforcing compliance.

Forced review and sanctions on content by administrative bodies carry significant risks. While administrative agencies must act swiftly to prevent physical harm, intervening in cultural or ideological matters risks compromising neutrality. Historical precedents, such as the controversial actions of the Ryu Hee-rim-led Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC), illustrate the dangers of administrative overreach in content regulation.

6. Should platforms that do not respond to removal requests be blocked nationally?

Blocking access to platforms that fail to comply with content removal requests could have significant consequences and might raise critical concerns. Platforms typically host user-generated content rather than their own, meaning that blocking an entire platform due to a few illegal items would also block a vast amount of legal content. Historical examples, such as India threatening to block Wikipedia over defamatory content or Brazil temporarily blocking WhatsApp due to legal disputes, highlight the disproportionate harm such measures can inflict on public access to information. In Brazil’s case, the Supreme Court overturned the blocking order, citing an undue infringement on citizens’ right to information.

Blocking platforms like Telegram would not solve the root issues and could significantly impact civil society organizations, including women’s rights groups, that rely on such platforms for communication and advocacy. Many organizations have years of essential data stored on these platforms, making an abrupt halt in their use impractical. Furthermore, the framing of the issue as “digital rights vs. women’s protection” exacerbates conflict without providing effective solutions.

It is crucial to remember that women’s digital rights are an integral part of broader digital rights. The challenge lies in protecting women’s dignity without undermining the principles of digital rights. A societal shift to reject the shaming of women’s bodies could be a long-term, transformative solution. Addressing the societal vulnerabilities that enable crimes like deepfake exploitation is essential, and society must collectively consider how to mitigate these issues at their root.

7. Should platforms that do not respond to removal requests be blocked nationally?

Boycotting Telegram could be a viable strategy, but it requires several conditions to be effective. For a boycott to succeed, there must be alternative platforms available, allowing users to transition without significant disruption. Currently, options like Signal provide some alternatives, but the limited diversity of platforms—dominated by Telegram and KakaoTalk—makes a boycott challenging. The example of Twitter’s transition to X under Elon Musk demonstrates that users will only migrate to alternatives when viable options exist. Ensuring platform diversity is critical to enabling boycotts as a practical approach.

It is also important to consider why civil society organizations adopted Telegram in the first place. Many shifted to Telegram from KakaoTalk to avoid government censorship. The same privacy features that make Telegram popular with privacy-conscious users also facilitate the proliferation of deepfake content. Boycotting Telegram may simply lead to the emergence of other platforms with similar features, without addressing the root issues of deepfake proliferation.

Additionally, a boycott is unlikely to significantly reduce the number of perpetrators of sexual violence. While well-intentioned users may leave Telegram, offenders have little reason to do so. Alongside a boycott, efforts must focus on empowering victims to report abusers and increasing solidarity with survivors. This can be achieved through strengthened sex education and media literacy programs, fostering a society that actively supports victims and challenges harmful behaviors.

*About the host: ‘People Outraged by the Nth Room Incident’ is an organization created by people who lost sleep over the Nth Room incident in early 2020. At a time when there were many restrictions on rallies and offline actions due to COVID-19, it was the beginning of ‘People Outraged by the Nth Room Incident’ to draw out individual citizens to express their anger through direct action. We have organized one-person protests at the National Assembly, courts, subway stations, etc. to condemn the Nth Room incident, and have planned and conducted press conferences, follow-up talks, rallies, and civic actions. After the Nth Room incident, we organized press conferences to condemn anti-LGBTQ remarks by lawmakers and public forums to discuss the Irida incident and AI ethics.

0 Comments