The following is Jiyoun Choe’s presentation at the TWIGF 2021 as part of a panel in the ‘Digital Human Rights in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic – An International Perspective’ session on December 10, 2021. (Created with Google Slides’ Matchday Theme)

TWIGF presentation – Jiyoun Choe

Hello! My name is Jiyoun Choe and I’m a Legal Counsel for Open Net based in Korea. I’m very honored and happy to be here today. I’m the last speaker before we start the discussion so let’s get right to it!

Being based in Korea, that will be the area of focus for this presentation.

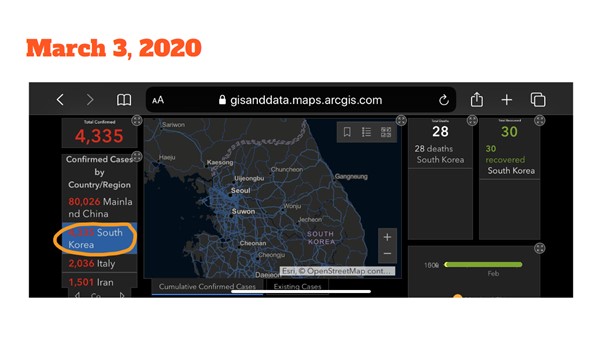

Towards the beginning of the pandemic when things were getting scary, I was in SF waiting to fly back home to Seoul. I would wake up every morning and nervously check the COVID map provided by Johns Hopkins and look at the numbers go up in South Korea.

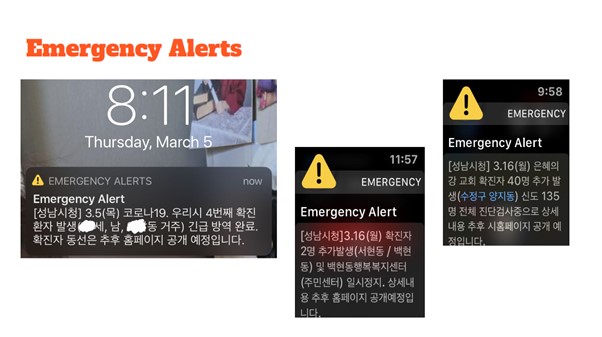

Once I landed in Seoul, I started getting these emergency alerts on my phone. They were data sent out based on the receivers’ location. It contained information about new confirmed cases of Covid. It mentioned the person’s age, gender, address. It also said to check the website for more information.

If you went to the website, the website looked like this. It listed every single Covid-19 patient and disclosed their gender, age, nationality, and if you clicked on their names, you would be able to see every location that they’d been to throughout the last 48 hours leading up to their positive covid results. It would even tell you if they were wearing masks at the location or not.

So how is this detailed accumulation and dissemination of personal information possible?

On the technological side, South Korea deployed a cell tower based id system. This meant that even with your GPS turned off, governments could compel telecommunication operators to provide mobile location information to track someone’s real time or past movements. It didn’t matter if you didn’t have a smartphone. As long as you had a phone, your location could be logged. Also, credit card use logs and cctv surveillance data was used.

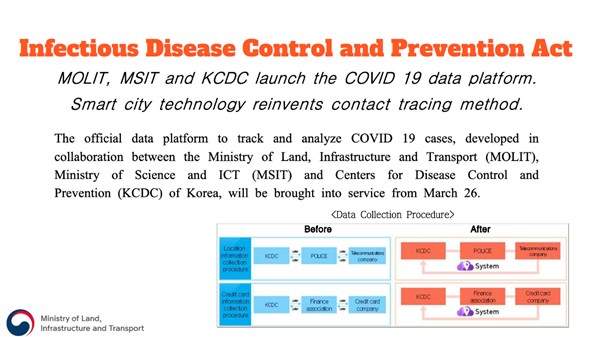

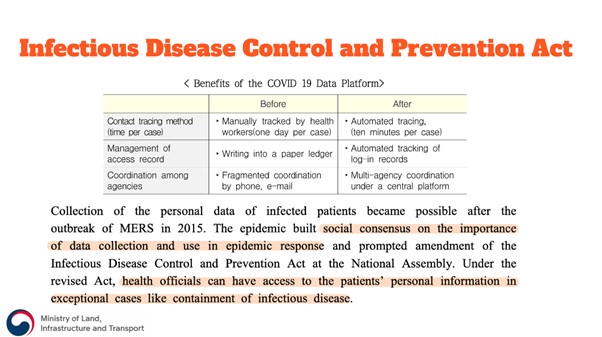

On the legal side, Korea has the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act. I’ll call it IDCP from this point on.

With some post-covid amendments, contact tracing became more automated.

The law laid the groundwork to make it possible for heads of government agencies to gain access to data of infected patients to be collected and used. It was amended as such following the 2015 MERS outbreak in Korea.

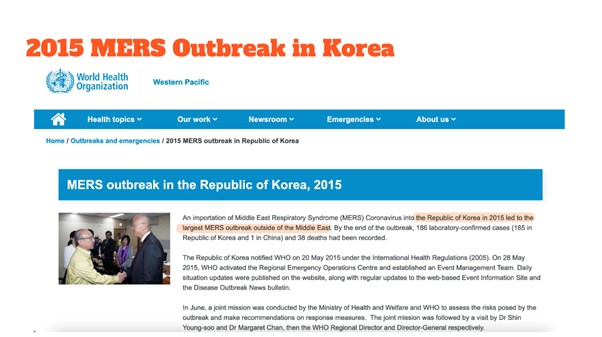

To briefly explain, in 2015 South Korea became the country with the largest MERS(Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak outside of the Middle East. There were a number of factors that led to this, but one main reason was that the government was hesitant in disclosing information about the location of the patients. It was decided that the location where the patients were being treated would be kept confidential. This led to people visiting the hospital for treatment of other illnesses and unknowingly contracting MERS and even dying from it. Public outrage was fierce.

It was also difficult to conduct contact tracing when a few patients were uncooperative in disclosing their whereabouts.

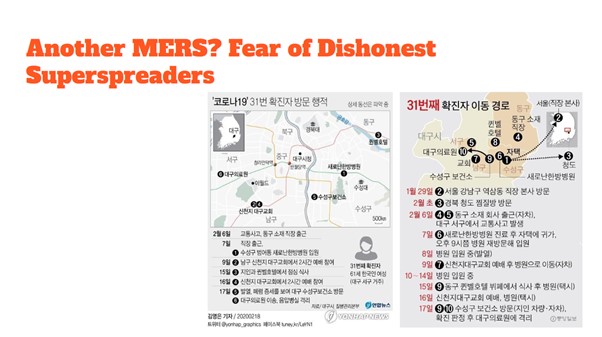

Fear of COVID becoming another MERS exploded when a few patients early on were dishonest about their whereabouts and ended up causing mass COVID infections. The patient in one case was afraid of revealing that she was a part of a religious group considered a cult by many, and as such, many of the people infected with covid around this time had to face public scrutiny of possibly being a member of a cult as well.

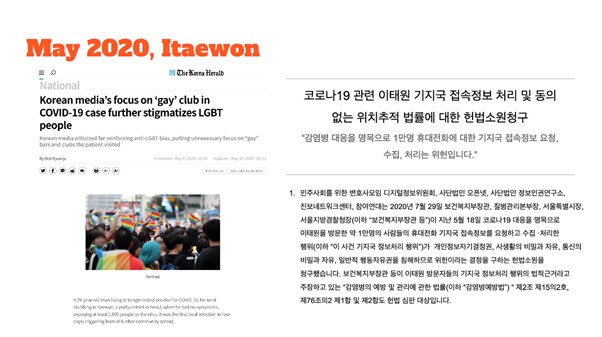

People’s fear of being called out and having their private lives exposed was very well grounded in the harsh reality. This next example shows the dire effects the above mentioned law (IDCP) can have on people. In May of 2020, someone who tested positive for covid turned out to have gone to a few clubs in the Itaewon area leading up to their positive covid test. (May 2). People of the internet found out that the clubs were LGBTQ clubs and the witch hunt began. It’s safe to say that South Korea is not accepting of the LGBTQ community. The individual was publicly outed because it was easy to find out who that person was with the information provided in the website. Where he worked, where he lived, his age.. that was more than enough information.

The somber incident gave us a peek into just how much personal information the government authorities were accessing in the name of disease control. Around 10,000 people’s location information based on cell-tower id was collected in the name of containing the Itaewon outbreak. For example, an individual who had visited a restaurant at the end of April 2020 received a text message from Seoul City on May 18 requesting them to get a Covid test. The individual hadn’t visited any clubs or even been in Itaewon around May 2. The individual had to face public scrutiny while getting their covid tests and was terrified of being identified. When they asked how Seoul City gained access to the relevant information, they were told that it was lawful under articles 76-2 paragraph 1 or 2 of the IDCP Act. The law makes it possible to collect information of not only patients of covid 19, but those suspected of contracting it.

Open Net and other civil societies jointly filed a constitutional complaint to the constitutional court of Korea claiming that the law infringes the people’s right to information self determination, right to privacy and free communication, among other rights. The court has not made a determination on the case yet.

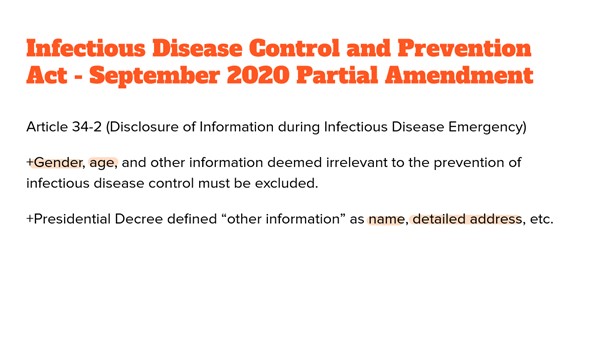

Recognizing these problems, the law was amended so that gender, age, and other information would be excluded in the disclosure of information. It is good to know that the National Assembly was proactive in fixing what needed to be fixed. Sadly it was a little too late for many whose lives were turned upside down for what some call “the greater good”.

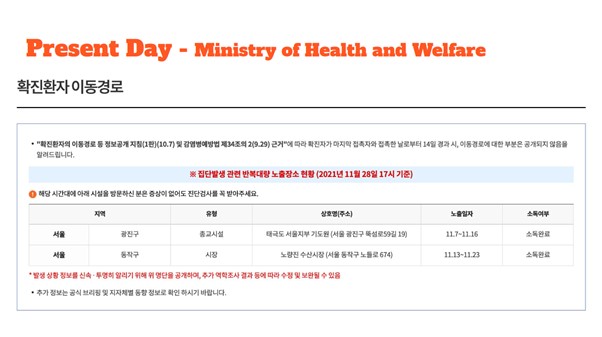

And as such, the website presently looks more like this. It lists only a few locations where mass outbreaks occurred, instead of listing all the individuals who caught covid.

Now, it’s time to move on to the international perspective. We’re here to learn about the national context of different countries and to combine what we know to head towards a better future.

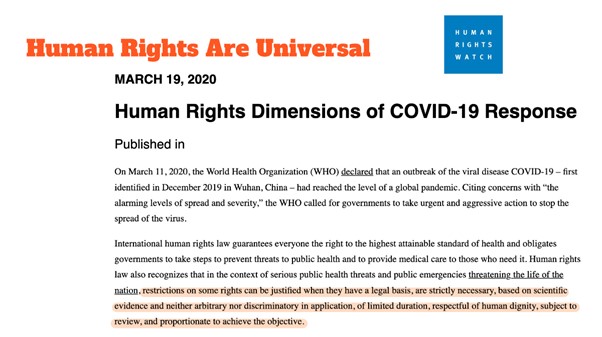

To do so, I think it’s important to keep in mind that human rights are universal. Human Rights Watch had a great series on COVID-19 so I used a screenshot of their website here. Shout-out to Human Rights Watch! What we choose to do from here on out should always have a legal basis, be strictly necessary, and proportionate to achieve the objective.

Also, everything that I talked about today about what happened in Korea can happen anywhere else in the world as well. The technology and the means to do it are all already there. Credit card information, location tracking-whether it be cell tower based or gps based-, cctv, are all present to differing degrees around the world. If you liked what you saw, or didn’t, it’s all possible in your area as well.

Lastly, I’d like to point out that there was a high level of consensus when it came to the collection of information in Korea. Even among the civil society groups, the outrage was focused on the dissemination of the information, not the collection of it. It was really interesting to learn about the differing degrees of public consensus in other countries and how the different governments’ policies were received by the people.

Thank you, and I look forward to the discussion.

0 Comments