Kyung Sin Park

Professor, Korea University Law School/Executive Director, Open Net Korea

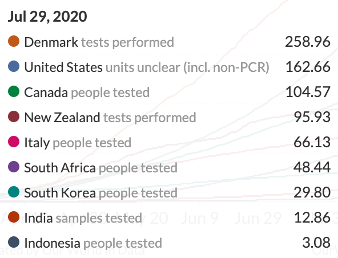

People have pointed to massive testing as reason for Korea’s success but as of July 29, 2020, Korea lags far behind the United States in terms of the number of tests done per 1,000 ppl. Korea’s test number is about 1/5 of the United States, less than 1/8 of Denmark, 1/3 of New Zealand, Canada, etc., and lags even behind South Africa. Except New Zealand, COVID-19 has not been contained by any measure in all the compared countries (see graphs below) – that is — despite the more massive testing than done in South Korea.

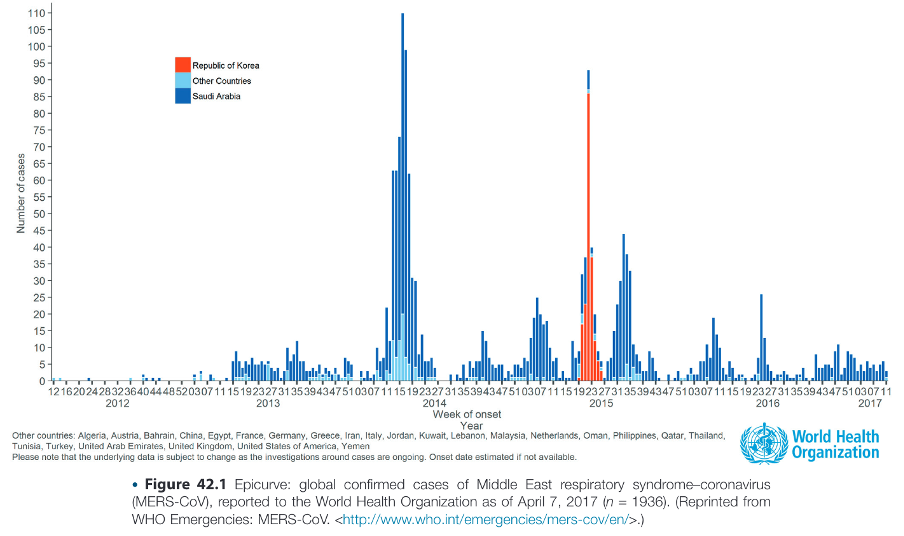

A more distinguishing feature of South Korea might be that she has focused its testing/notification resources to people who might have been exposed to contact with patients. This art of identifying and notifying probable contactees is called contact tracing. Manual contact tracing takes time and efforts that may be available only after the contactees have further reproduced the virus to others, and relies on voluntarily confessed memories of the patients whose inaccuracy has great repercussions on the efficacy of containment efforts. Actually, it is those repercussions during the 2015 MERS attack (see figure) that has actually prompted the Korean legislature into the country’s unprecedentedly privacy-invasive contact tracing law based on cell site location information.

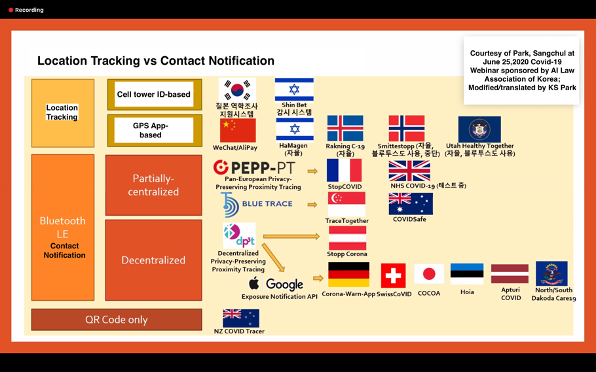

Other countries have engaged in contact tracing but only on the basis of consent because of privacy concerns and therefore its efficacy has been severely limited by the people’s willingness to install the tracking apps. Such voluntary contact tracing app suffers from the double problem of firstly not being able to verify the location (relative or absolute) of those patients without the apps and secondly not being able to notify those probable contactees without the apps. No country has reported significant success from the voluntary app.

As you can see from the above figure, South Korea and Israel are the only ones that instituted mandatory location tracking (at least for all those carrying mobile phones) using cellphone location information, whose efficacy was noted very early.[1] However, Israel has shut down the use of that system after the Supreme Court’s decision in April and has resumed only for 3 weeks in July.[2] All other countries’ location tracking are based on the apps that people need to download to be part of the contact tracing system. Poland has used mandatory location tracking based on cell site data but not to a great success yet.[3]

Privacy concerns with mandatory contact tracing are no doubt grave. Most of the media and policy attention on privacy concerns have been on public disclosure of the infected person’s movements, resulting in the country’s National Human Rights Commission’s action and the consequent restriction on the scope of information disclosed.[4] However, it seems that what has been critical in making Korea’s targeted testing more effective is the initial government acquisition of the location data of the infected persons and others in vicinity, rather than the disclosure thereafter.[5] Although public disclosure of the patients’ movements is supported by 90.3% of the public but only 59% of the respondents actually use the information.[6]

Given that the public announcements of patient movements reach only half the people, what has made Korean system effective is that the law (Article 76-2 of Infectious Disease Prevention Act) authorizes the location check of not just patients and suspected patients but also people who are merely “suspected of being in contact with patients” (‘suspected contactees’, hereinafter). Contact tracing traditionally consists of two steps: (1) location tracking of patients; (2) notifying people who were in contact with patients. The second, notification step has been usually done through public disclosure (or notification by publication). However, the Korean authorities used the location tracking law not just for the first step but also for enhancing the effectiveness of the second step. Instead of tracking the location of known targets, the authorities conducted cell tower search to identify the targets for notification and send private SMS texts or other messages directly to the suspected contactees. It means that Korean law solves both the problem of checking the movements of patients and that of identifying and notifying suspected contactees.

The privacy concern with the thus described Korean government’s acquisition of location data is clear: if similar actions take place in the U.S. context, we can predict what objections may be registered. The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution restricts any state intrusion into “reasonable expectation of privacy”[7] with the procedural requirement of ‘warrant based on probable cause (to believe that a crime has been committed and the incriminating evidence is at/with the place, thing, or person to be searched).’ Checking the location of a private person has been usually done through cell site location tracking, which involves acquisition of the pen register or trap and trace information, which in turn has been by and large subject to the restrictions of under Electronic Communication Privacy Act: Records stored by a wireless service provider that detail the location of a cell phone in the past (i.e., prior to the entry of a court order authorizing government acquisition) are known as “historical” cell site information. It can be obtained using a subpoena or warrant, upon a demonstration of “reasonable grounds to believe” that the information is “relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.”[8] Given that the Korean government engages in location tracking of patients or identification of suspected contactees without any procedural requirement such as court orders, any non-consensual and non-judicial location tracking or cell tower search is likely to be considered too privacy-invasive.

However, given the unprecedented magnitude of the pandemic, there have been theoretical discussions to emulate the invasive contact tracing in the West despite the privacy concerns.[9] Such proposals came from consumer rights advocates[10], privacy advocates[11], and even privacy advocates based in Europe where the General Data Protection Regulation rules.[12] Also, Congressional Research Services engaged in legal discussion over the use of mandatory non-judicial location tracking for COVID-19 mitigation purposes and pointed out the potential significance of the “special needs” doctrine or the “administrative search doctrine” as a possible constitutional justification.[13] Other commentators also agreed that the “administrative search” doctrine may justify the mandatory location tracking for COVID-19 purposes.[14]

Privacy is not the only reason that mandatory location tracking through cell site information is being rejected in the U.S. From early on, it was pointed out that cell site location information was deemed not granular enough to detect the critical less-than-6-foot distance.[15] However, the Korean system solved this problem by casting a wider net (or erring on the side of caution), i.e., including in the contact tracing those who were not within the 6-foot distance of a patient. In a dramatic episode, the City of Seoul, upon finding a patient in a nightclub in the city’s clubbing hotspot, did cell tower search and identified all of about 10,000 phones that remained in the area for more than 30 minutes on the night that the patient visited, and sent SMS texts to all of them overnight, requiring to come and get tested even anonymously if needed.[16]

[1] Kelly Servick, “Cellphone tracking could help stem the spread of coronavirus. Is privacy the price?”, Science, Mar. 22, 2020

[2] Tehilla Shwartz Altshuler and Rachel Aridor Hershkowitz , “How Israel’s COVID-19 mass surveillance operation works”, Brookings Techstream, July 6, 2020

[3] Katitza Rodriguez, Svea Windwehr, Seth Schoen, “International Proposals for Warrantless Location Surveillance To Fight COVID-19”, Electronic Frontiers Foundation, MAY 21, 2020

[4] Mark Zastrow, “South Korea is reporting intimate details of COVID-19 cases: has it helped?”, Nature Briefing, 18 March 2020

[5] Helen Chan, “Pervasive personal data collection at the heart of South Korea’s COVID-19 success may not translate”, Reuters, 26 March 2020.

[6] Yonhap News Agency, “90% of Users Find Disclosure of Patients’ Location Data ‘Appropriate’” (Korean), May 18, 2020, https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20200518072400017

[7] Katz v. United States, 389 U. S. 347 (1967)

[8] In re the Application of the United States for an Order Authorizing the Installation and Use of a Pen Register, 402 F. Supp. 2d. 597, 599 (D. Md. 2005). 18 U.S.C. § 2703(d).

[9] Cristiano Lima and Vincent Manancourt, “Privacy agenda threatened in West’s virus fight”, Politico, April 5, 2020.

[10] Justin Brookman, director of consumer privacy and technology policy for Consumer Reports, interviewed in Lima, supra.

[11] Maciej Ceglowski , “We Need A Massive Surveillance Program”, Blog, 03.23.2020,

[12] Max Schrems, interviewed in Lima, supra.

[13] Congressional Research Services, COVID-19, Digital Surveillance, and Privacy: Fourth Amendment Considerations, April 16, 2020

[14] Alan Z. Rozenshtein, “Disease Surveillance and the Fourth Amendment”, Lawfare, April 7, 2020.

[15] Susan Landau, “Location Surveillance to Counter COVID-19: Efficacy Is What Matters”, Lawfare, March 25, 2020.

[16] Reuters, “South Korea investigators comb digital data to trace club coronavirus cluster”, May 12, 2020.

![[Rightscon 2025 Taipei] SEACPN on Content Moderation](https://www.opennetkorea.org/wp-content/uploads/et_temp/Screen-Shot-2025-03-16-at-1.09.36-AM-218207_1080x550.png)

0 Comments