“Ask Your Telcos” Campaign Report:

2-Years Fight against Warrantless Seizure of Subscriber Information

Introduction

Ask Your Telcos campaign is an advocacy campaign launched by Open Net in January 2015 whereby the subscribers of three major telecoms in Korea (SKT, KT, LGU+) make inspection requests to the telcos on their data and on whether, when, to whom, and for what purpose, their data has been disclosed to third parties including investigative authorities. The campaign is designed to put pressure on the telcos to stop complying with the police requests of warrantless seizure of subscriber identifying information.

Background

Legal Landscape

Under Article 83(3) of the Telecommunications Business Act (TBA), telecommunications business operators “may comply” with the requests from judicial and investigative authorities for their subscribers’ information such as names, Resident Registration Numbers (RRNs), and addresses. The request is made directly to the businesses, and no due process is required.

This convenient and time-saving process of securing personal information of the subscribers has been in existence before the heavy data protection regime was introduced under the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA) or the Information and Communications Network Act (ICNA). It seems inevitable that the process is more and more favored by the law enforcement with ever strengthening of the data protection regime.

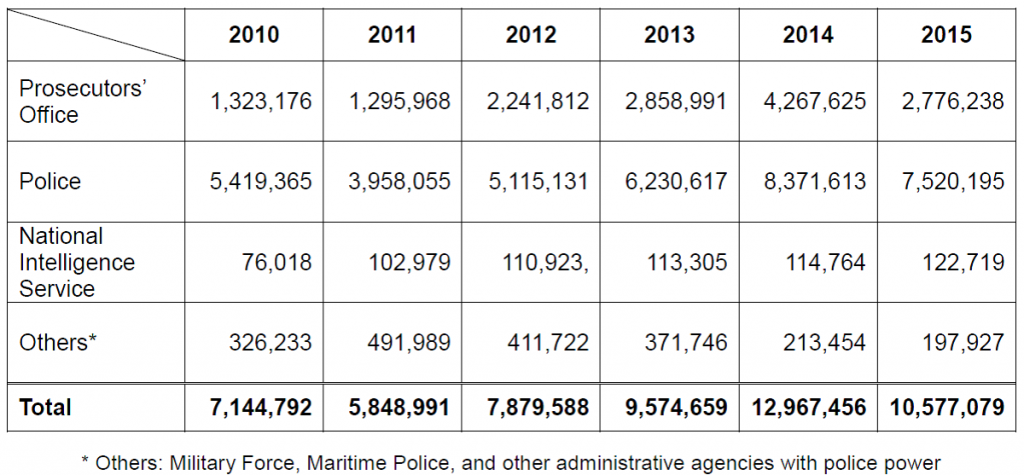

Figures clearly prove this tendency. When Korea is roughly a country of 50 million people, about 6 million people’s subscriber information was accessed by investigative authorities in 2011. That number has more than doubled to reach close to 13 million in 2014.

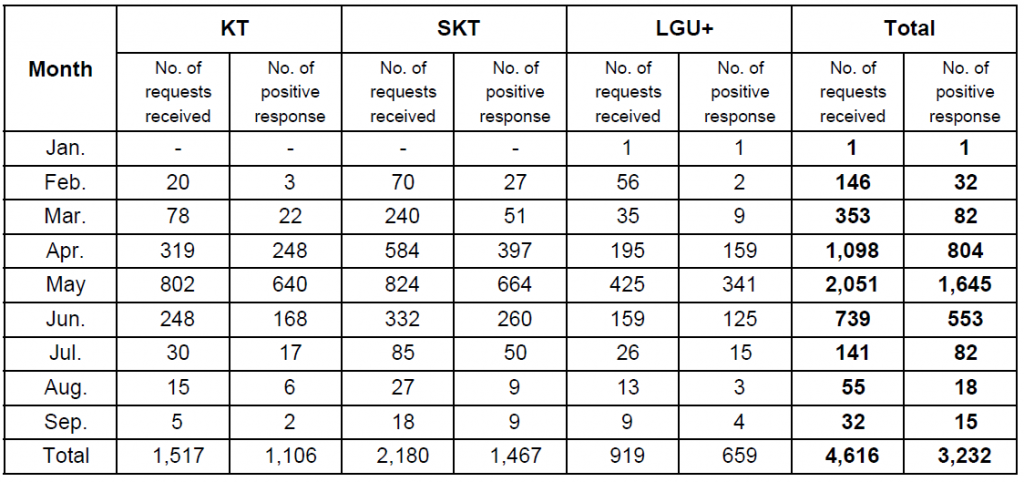

<Number of Warrantless Seizure of Subscriber Information1>

In the meantime, the Korean National Human Rights Commission decided in April 2014 that the provision should be repealed so that the investigative authorities’ access to subscriber information is governed by the process under the Communications Secrets Protection Act which requires warrant from the court.2 The Commission stated that the process significantly infringes on subscribers’ privacy as their personal information is furnished without consent and post-notification. This renders the data subjects defenseless, when thus obtained data may be used to bring criminal charges against them. Moreover, the data is used to identify individuals without any constraint and therefore facilitates mass-surveillance.

Series of Legal Actions

The PSPD Law Center3 filed a constitutional challenge against Article 83(3) of the TBA, for violation of the “warrant” doctrine set forth in the Korean Constitution. The Constitutional Court dismissed the constitutional challenge in August 2012 stating that the provision merely allows the operators to make the disclosure and does not require them to do so, and therefore there is no “state action” involved in what the Court believed to be “voluntary acts of the telecommunications operator.”

Upon hearing that warrantless disclosure is not the doings of the state but the doings of the company, the PSPD Law Center promptly filed a damages suit against a major web portal “Naver” for making such “voluntary” disclosure on a high profile case involving the defamation investigation into a Youtube video clip4 featuring the then cultural minister and the international figure skating star Yuna Kim. After losing in the court of first instance, they won a damage award of KRW 500,000 in the Seoul High Court on 18 October 2012.5 Within two weeks, all major web-portals and Internet companies stopped altogether complying with Article 83(3) requests.

However, the telcos, responsible for about 90% of subscriber data disclosure in Korea, insisted on continuing to comply with Article 83(3) requests. What is more, they refused to disclose to their customers whether the Article 83(3) data disclosures have been made. In April 2013, PSPD Law Center filed another lawsuit forcing the telcos to reveal whether they have made subscriber data disclosure under Article 83(3) and won again in the Seoul High Court in January 2015. The decision imposed damages of about KRW 200,000-300,000 for each instance of refusal to disclose.6 The main reasoning of the High Court was based on users’ rights to demand disclosure (inspection) on how their personal information is used and shared under Article 30(2) of the ICNA.

Launch of “Ask Your Telcos” campaign

Open Net Korea and PSPD launched “Ask Your Telcos” campaign in January 2015 following the High Court decision. KakaoTalk scandal in October 2014 increased public awareness on the pervasiveness of the state level mass-surveillance, and this timely campaign received much attention from the media and the public.

As aforementioned, telcos had been refusing to disclose to users whether the data disclosure have been made. However, as a result of “Ask Your Telcos” campaign, telcos began to provide the process for the disclosure requests. Around 4,600 requests were made during the eight-months period from January to September 2015. It was found that many of the people directly or indirectly involved with the Sewol ferry disaster, including the victims’ families, protesters, and journalists, had their information accessed by the investigative authorities including the NIS during the period following the disaster.

Observation of UN HRC

The UN Human Rights Committee considered the fourth periodic report of Korea of its compliance with ICCPR in October 2015. Open Net Korea, as one of 84 NGOs that contributed to the NGO Submission, expressed its concern with the warrantless access to subscriber information and also attended the review session held in Geneva. In its Concluding observations adopted on 3 November 2015, the Committee showed its concern for the government surveillance:

Anti-Terrorism Bill and year 2016

The campaign gained a new momentum in early 2016. After November 2015 Paris attacks, President Park started to urge for the passage of the anti-terrorism bills pending at the National Assembly. On 23 February 2016, National Assembly speaker CHUNG Ui-hwa asserted his authority on to bring the anti-terrorism bill to the floor for a vote, and despite the opposition parties’ 9-day long filibuster, the majority Saenuri Party passed the Anti-Terrorism Act on 3 March 2016 with only one MP from the opposition present. During the controversial three-month period, many people including journalists, activists, and laypersons made disclosure requests to telcos and a number of National Assembly members of the opposition parties claimed that their data was accessed without apparent reasons. Several civic groups launched their own campaigns, and Minbyun (Lawyers for a Democratic Society) filed a constitutional challenge against the provision in April 2016.

Unfortunately, the legendary 2012 Seoul High Court decision awarding damages for complying with data requests was overturned by the Supreme Court in March 2016. However, the Supreme Court left a silver lining in its decision by stating that when the request was clearly illegal, the data subject may hold the investigative authority accountable. Following the Supreme Court’s logic, Open Net filed a lawsuit claiming civil damages against the NIS, the Police, and the Prosecutors’ Office on behalf of 22 plaintiffs who participated in “Ask Your Telcos” campaign.

Methodology

Introduction

Open Net and PSPD launched “Ask Your Telcos” campaign on 30 January 2015 right after the Seoul High Court decision imposing damages on three major telcos for refusing to disclose to the plaintiffs whether they have made Article 83(3) data disclosure. Main objective of the campaign was to put pressure on the telcos to stop complying with the police requests of warrantless access to subscriber information because the more people appear with confirmed warrantless access, the more legal exposure the telcos will come under at the rate of KRW 500,000 per person according to the 2012 High Court decision. Open Net also submitted a bill abolishing the provision through MP JUNG Cheong-rae in 2014.

Phase 1 (January – May 2015)

Open Net posted an instruction manual on its website (http://opennet.or.kr/8453) on how to make a request for each telecom (SKT, KT, and LGU+), and stated that any person interested in participating in an impact lawsuit to send the responses to Open Net. The legal foundation of disclosure requests is Article 30(2) of the ICNA which provides users the right to request inspection of: 1. his/her personal information held by telecommunications service providers; 2. How the personal information was used by the service providers or whether it was shared with a third party; and 3. records of users’ consents given for collection, use, or sharing of personal information.7

For the first few days, telcos refused to make the disclosure and had to be educated about the court decision. It took nearly two weeks for telcos to implement a stable system to process the requests since the launch of the campaign. This was a remarkable progress, but the telcos made users visit offline stores or customer service centers during office hours to make a request and then to get the response, which made participation very limited.

Open Net put pressure on the telcos by reporting them to the Korea Communications Commission for the violation of Article 30(6) of the ICNA prescribing that the method of requesting inspection must be easier than the method of giving consent to the collection of information. The KCC set up a roundtable with Open Net and three telcos in April and the telcos promised to make improvements. Few months later, each telco set up an online request system.

From February to May 2015, 65 people participated in the campaign by sending their responses, and among 65, 21 people found that their subscriber data were accessed by investigative agencies. There has been no participants since May 27 in year 2015. In September 2015, Open Net received the following statistics through MP YOO Seunghee (as of 22 September 2015):

The table shows that more than 4,600 requests were made during the eight-month period from January to September 2015.

Phase 2 (February – April 2016)

“Ask Your Telcos” campaign gained a new momentum during the opposition movement against the anti-terrorism bill. It was found that the telcos finally made the process much easier by allowing users to make requests thoroughly online. Open Net manual was shared on Facebook for almost 6,000 times. Many civic groups joined a coalition led by the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions in launching a separate campaign, several liberal newsmedia participated and promoted the campaign, and numerous individuals voluntarily shared the instructions. News about people who got their data accessed broke out almost every day. During the three-month period, 46 people participated in Open Net’s “Ask Your Telcos” campaign by sending their responses from telcos, and 36 people had positive responses.

Results and Findings

“Ask Your Telcos” campaign was timely and successful. Now the users can easily make online requests to find out whether their subscriber information was warrantlessly accessed by the investigative authorities. However, it did not stop telcos from complying with the warrantless requests. Moreover, telcos claim that they only retain such details for a period of one year, which is a minimum retention period required by the law. Therefore, users will never know if the access happened more than a year ago. And the reason for access is not clearly stated in the telco’s response, and telcos are refusing to disclose the written request received from the authorities where the reason for request supposed to be stated. Open Net is pursuing after the investigative authorities in the civil lawsuit to figure out ways to access the documents and prove that there has been extensive abuse of the system by the state for mass-surveillance.

———————————————————————–

1 The statistics is disclosed semiannually. See official Site of the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning, http://www.msip.go.kr/web/main/main.do

2 http://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2014041611218282360 (Korean)

3 K.S. Park as Executive Director of PSPD Law Centre, who has directed the lawsuits described here, later founded Open Net Korea in 2013.

4 YouTube (March 18, 2010), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X5OOD72-MzA

5 Seoul High Court, 2011Na19012, October 18, 2012

6 Seoul High Court, 2014Na2020811, January 19, 2015

7 According to Article 35 of the PIPA, a person may make a data access request (“inspection”) to any company or government agency, and the requested agency must answer within 10 days at the penalty of a fine not exceeding KRW 50m. The law also provides request forms. For telcos and Internet intermediaries, the ICNA applies even a shorter timeline, i.e., “without delay” – therefore shorter than 10 days, under its Article 30. Also, under Article 30-2, companies larger than certain scale must periodically notify users about their personal information utilization even without any request, at the penalty of a fine not exceeding KRW 30m.

0 Comments